1938–1943

Hedda Sterne called Surrealism “the greatest influence in my life when I was young.” Raised in Bucharest, Vienna, and Paris in the 1920s, Sterne closely followed the post-Dada movements of Constructivism and Surrealism. By the late 1930s and into the 1940s, she regularly exhibited within the Surrealist context, including the influential “First Papers of Surrealism” organized by Marcel Duchamp and André Breton, and at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery.

1943–1947

Hedda Sterne arrived in New York in 1941 as a refugee of WWII. Within a year of her arrival she had begun a new series of work based on memories of her childhood in Bucharest. But Sterne’s focus soon shifted toward her new surroundings.

“I became totally enthralled visually with the United States, so I became like a premature Pop artist. I started painting my kitchen, the kitchen stove, the bathroom appliances, everything where I lived. Then I went out and I painted Ford cars and the Elevated. And then I went to the country and I started painting industrial machines, and then I painted the roads. I became visual when I came here.”

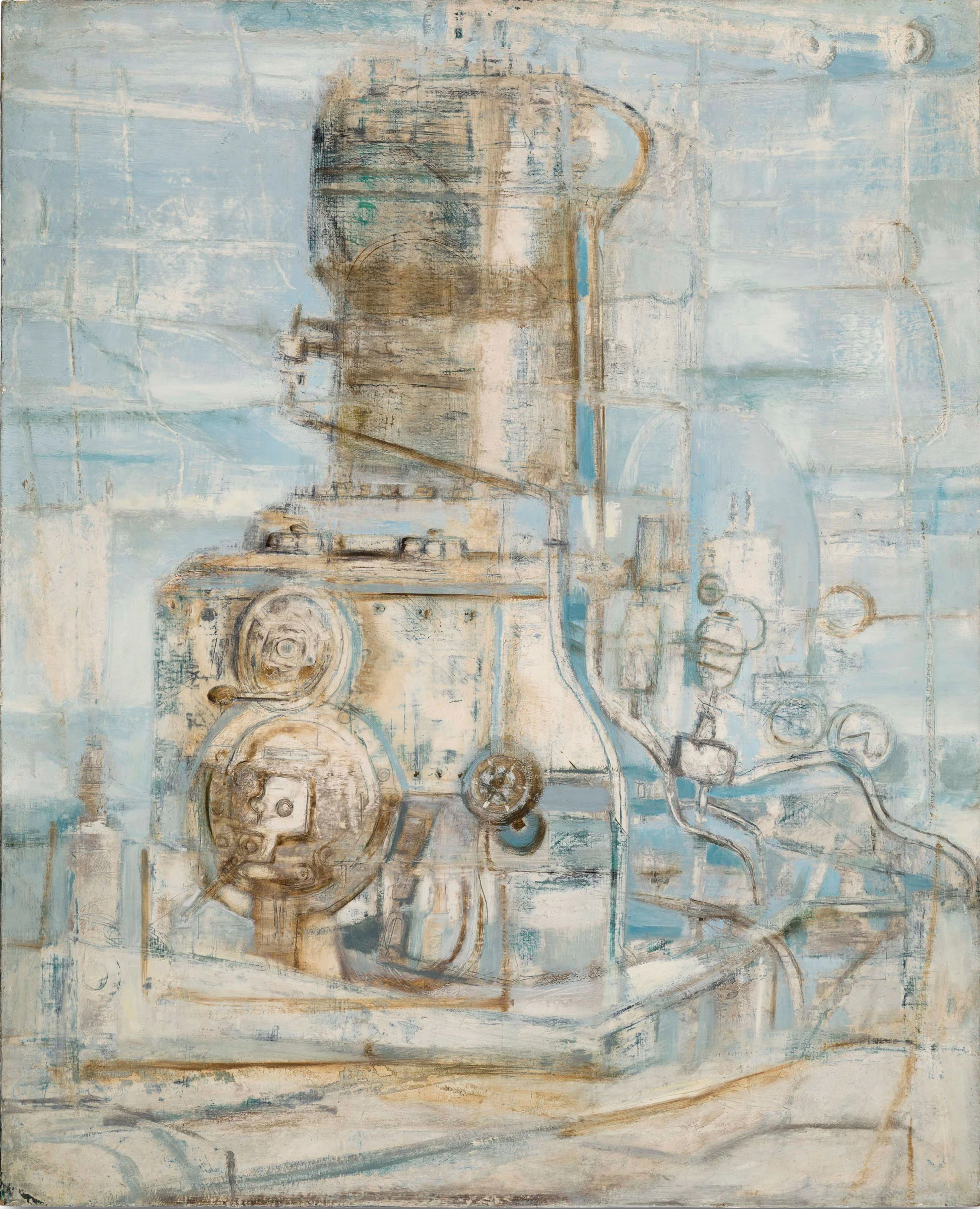

1947–1952

Hedda Sterne described her impression of the United States in the 1940s as “more surrealist, more extraordinary, than anything imagined by the Surrealists." She was particularly drawn to anthropomorphic qualities of machinery, from rural farm equipment in Vermont to massive construction cranes in New York. Her “anthropographs” reflected a feeling that machines are “unconscious self-portraits of people’s psyches.”

Hedda Sterne, Machine (Anthropograph I), 1949, Oil on canvas, 29 1/2 in. x 39 in., Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Purchase, Gift of Samuel Dretzin, by exchange, Bequest of Gioconda King, by exchange, Rogers Fund, by exchange, Funds from various donors, by exchange, and Gift of Chauncey Stillman, by exchange, 2017

1952–1958

Hedda Sterne described feeling that New York in the 1950s was “like a gigantic carousel in continuous motion — on many levels — lines approaching swiftly and curving back again forming an intricate ballet of reflections and sounds.” She added aerosol spray paint — new to hardware store shelves in the early 1950s — to many canvases to emphasize motion and light, and because, as she later explained, “it could not be done in skywriting with jet planes.”

1958–1965

Hedda Sterne’s work of the late 1950s took on a distinctly less urban motif, inspired by various landscapes encountered while traveling. While living in Venice, Italy in 1963 and 1964 on a Fulbright fellowship, her previously frenetic abstractions became still, atmospheric lines conveying deep space.

“I get enormous pleasure out of very small contrasts. I don't know to what extent it is an emotional experience or an intellectual pleasure. You know there are knife-edge contrasts in my ‘Vertical-Horizontal’ pieces. This is what I enjoy — these very, very subtle distinctions in values.”

1965–1969

In the mid-1960s, Hedda Sterne began a large series of work exploring the juxtaposition of organic forms and atmospheric space. She used a range of “unforgiving” techniques, such as thinned acrylic paint poured onto raw canvas and continuous line drawings made with Rapidograph technical pens. These practices helped her to loosen control over the content of her work and discover “secret significance in the depth of the ordinary.”

1969–1981

By the late 1960s, Hedda Sterne’s automatic drawings began to reflect her long-standing interest in the face and figure. Though primarily recognized for her abstractions, Sterne embraced this new turn, creating drawings and paintings of faces, figures and crowds. Particularly fascinated by the symbolic potential of a few lines and shapes, she created a large-scale installation of anonymous painted faces titled Everyone.

“When I do these faces the way I do, to me it’s like using the most simple, easily understandable language there is.”

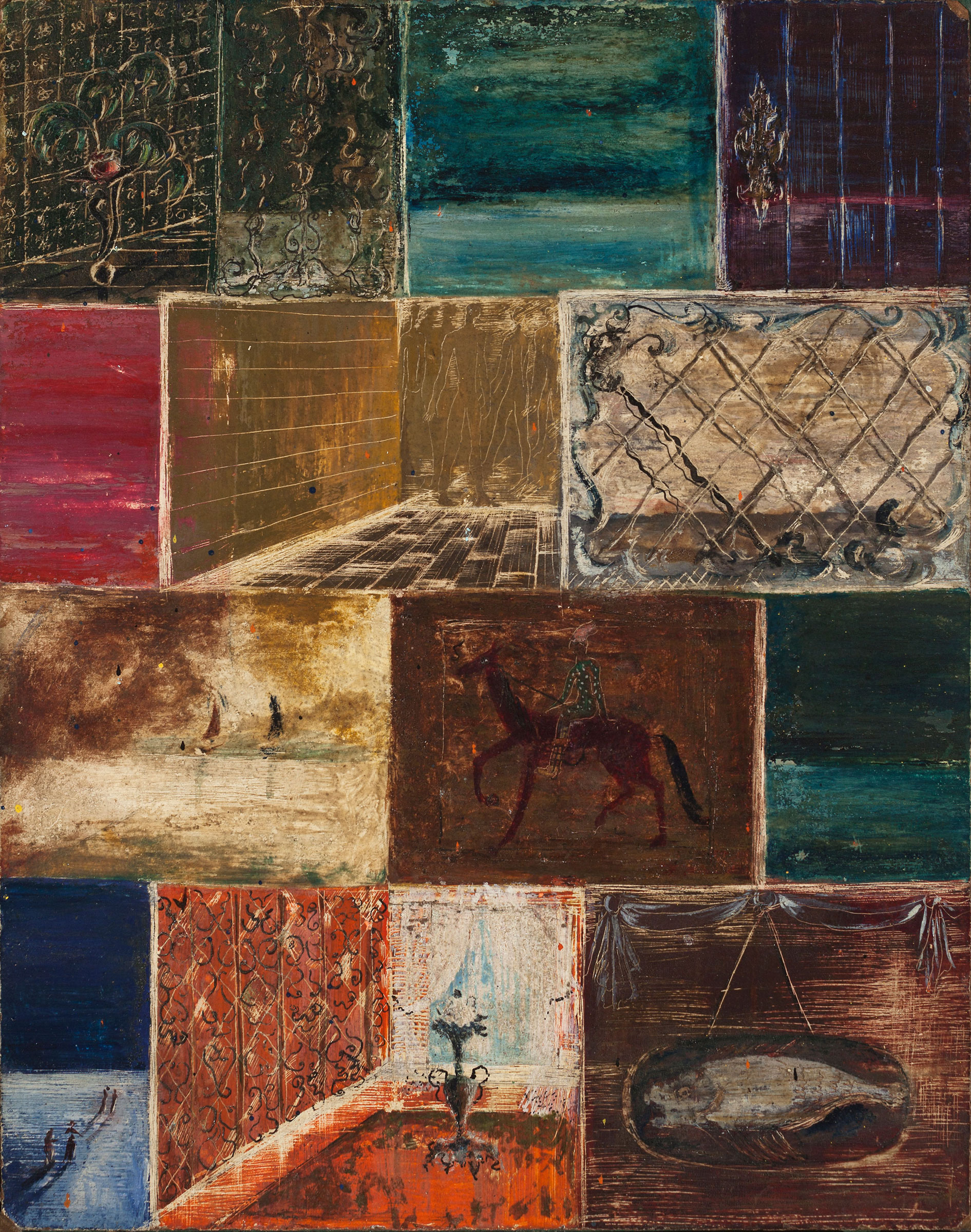

1981–1990

Dore Ashton wrote of Hedda Sterne’s process that “always the observed eventually is subsumed by the metaphorical impulse, which draws wider and wider circles around a theme once it is deposited in her imagination.” Sterne’s geometric paintings and drawings of the 1980s synthesized her decades-long exploration of light and space (landscapes and interiors), with a growing interest in symbolism and modes of perception.

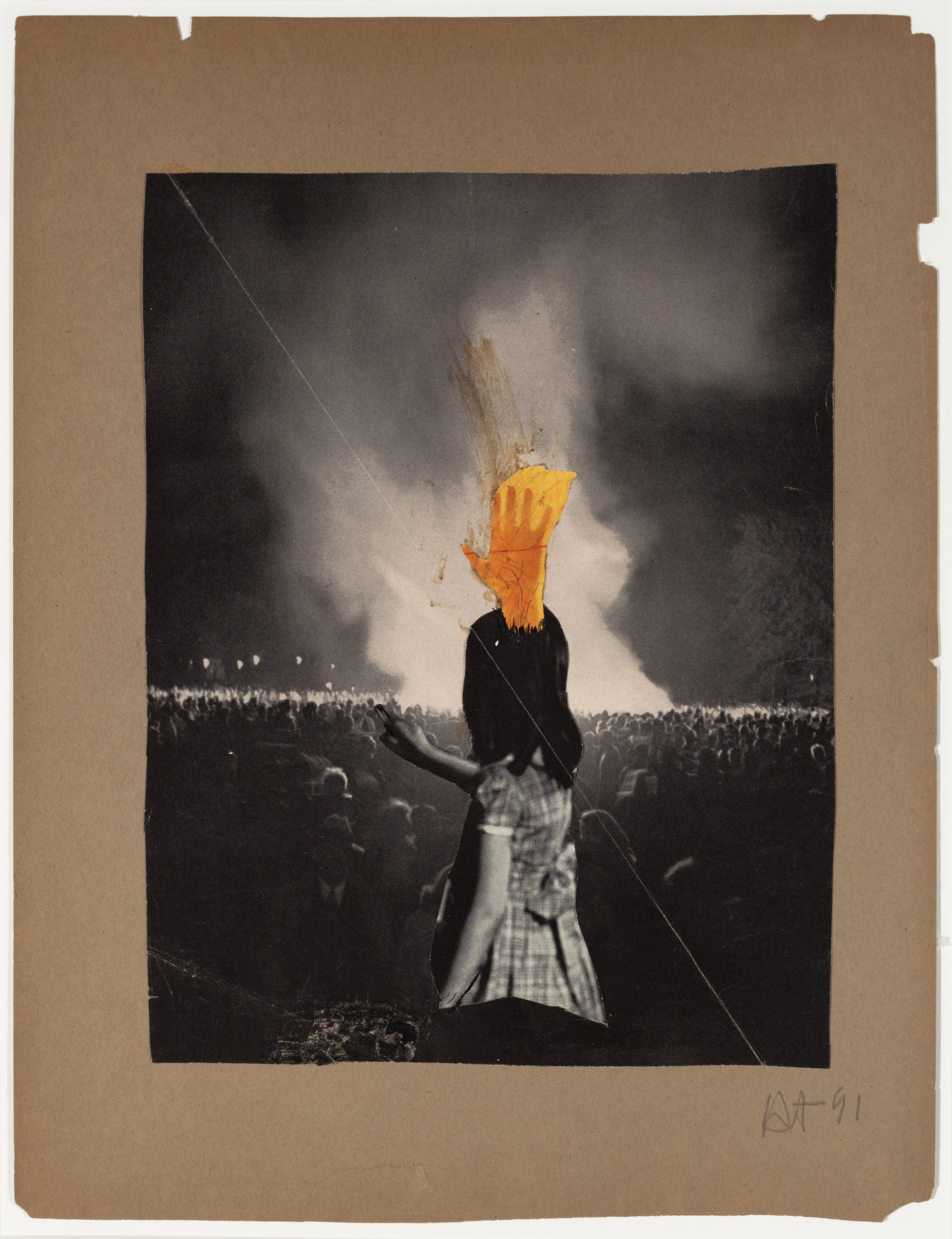

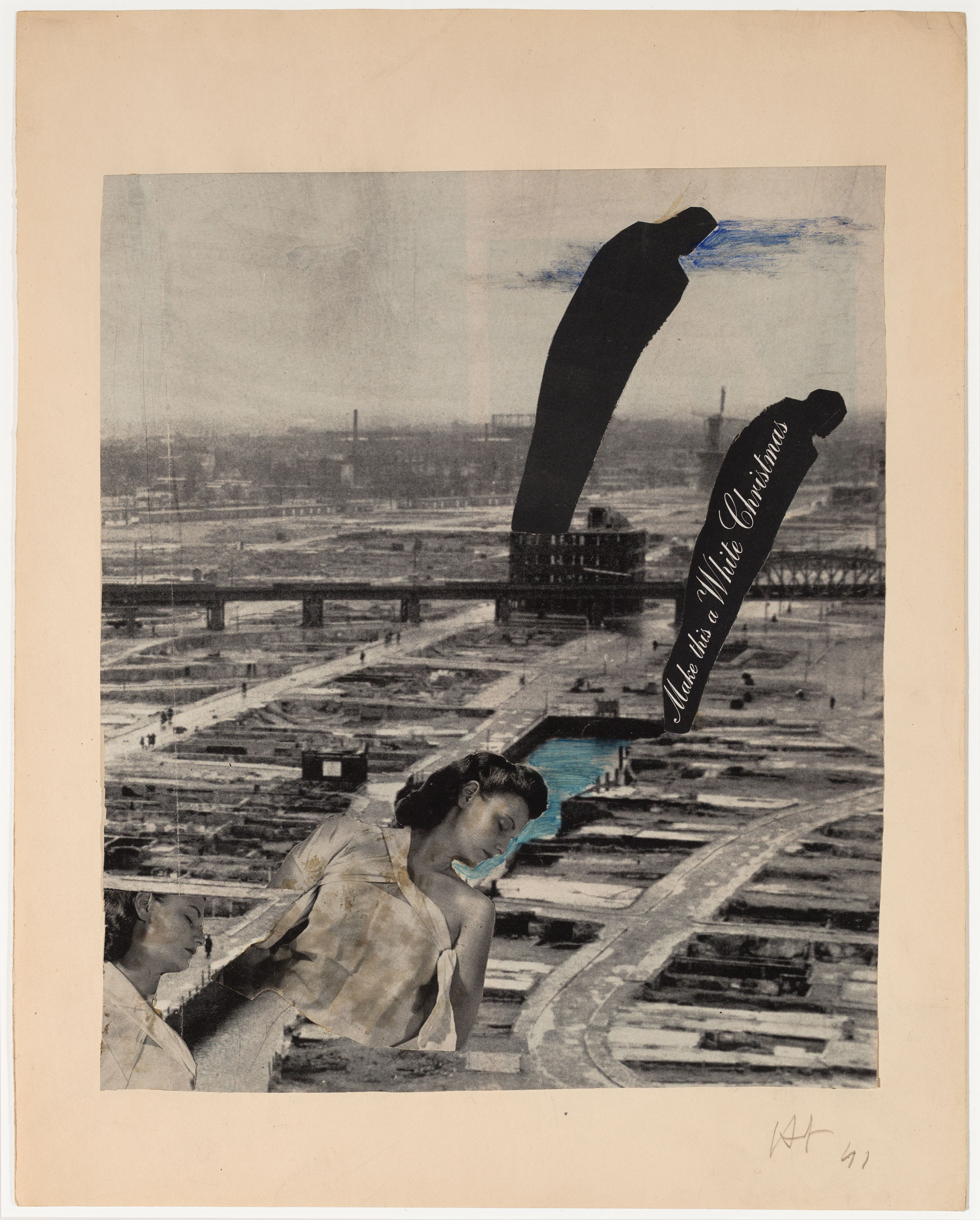

1990–1998

By the early 1990s, Hedda Sterne’s paintings began again to feature wavering, organic lines, some interrupting the rigid architectural structures common in her work of the prior decade. She began a new series of automatic drawings, allowing her hand to act without preconception.

“Sometimes I react to immediate visible reality and sometimes I am prompted by ideas, but at all times I have been moved, to paraphrase Seamus Heaney, by the music of the way things are.”

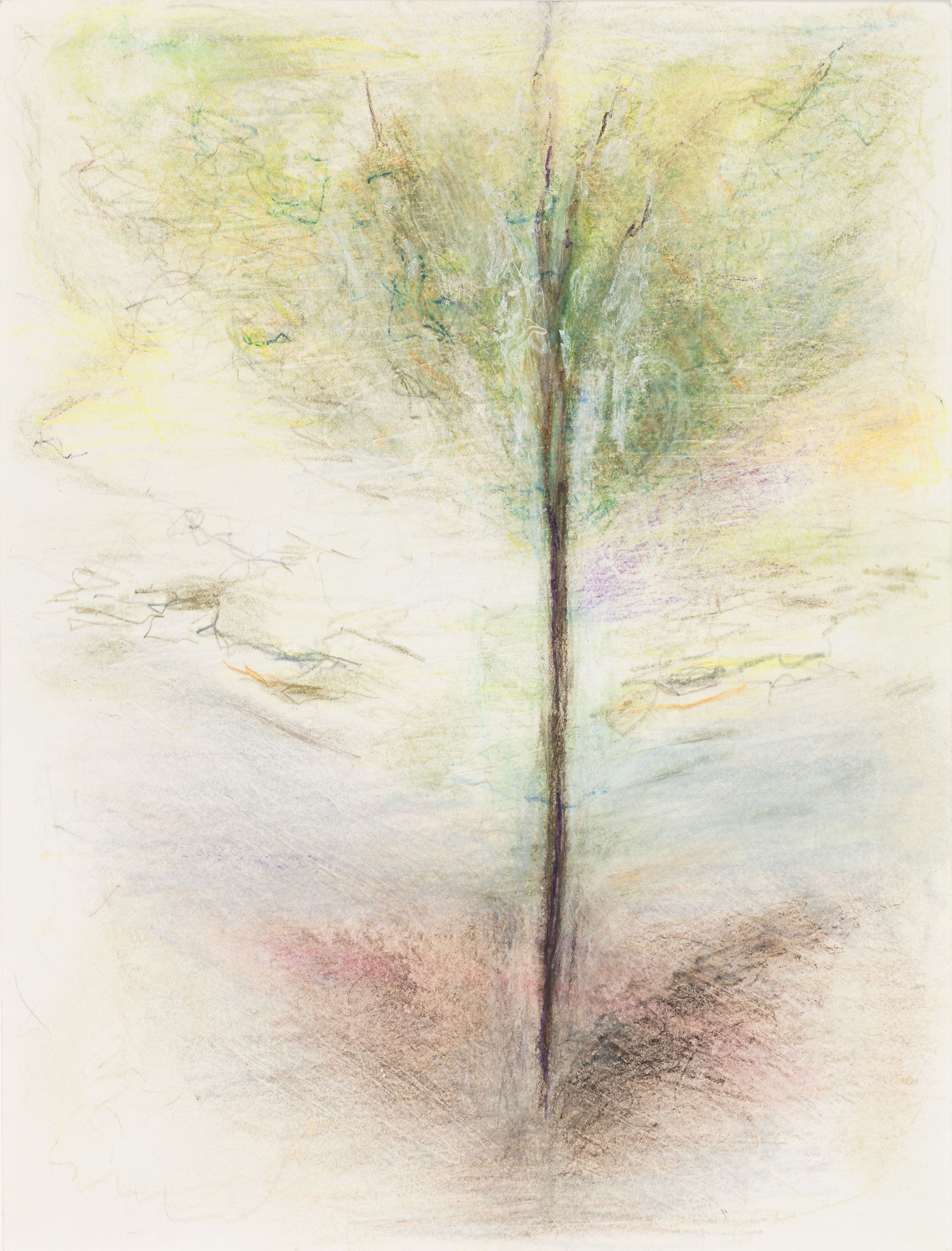

1998–2007

In 1998, Hedda Sterne quit painting, limited in motion and by macular degeneration. However, rather than cease working altogether, Sterne created one of the most prolific series of her long career, using graphite, pastel, and sometimes Wite Out on thick sheets of paper.

“With time I have learned to lose my identity while drawing and to act simply like a conduit, permitting visions that want to take shape to do so.”

![Hedda Sterne, Portrait of Saul [Steinberg], 1943, Graphite on paper, 12 in. x 8 3/4 in.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/586d344215d5dbe77c2087cf/1494345446206-ETD0P3RFU8YOZUMXQ8DG/hedda-sterne-drawing-0254.jpg)

![Hedda Sterne, Untitled [ Airplane cockpit ] , 1949, trace monotype, 15 7/16 × 10 3/8 in., Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Print Committee 2007.11](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/586d344215d5dbe77c2087cf/1494346255340-8F302GXLB9IUOH884PSJ/hedda-sterne-monotype-whitney.jpg)