Automatism

Hedda Sterne was deeply influenced by the Surrealist movement as a young artist in Europe and it left a lasting impression on her work. Surrealist automatism — the practice of allowing artwork to develop without conscious control or intention — was an essential part of her artistic practice throughout her life, from chance collage to automatic drawing. Sterne described the feeling of losing her identity while drawing and becoming “simply like a conduit, permitting visions that want to take shape to do so.”

The Everyday Surreal

When Hedda Sterne arrived in New York in 1941 as a refugee of WWII she felt surrounded by a world “more extraordinary than anything imagined by the Surrealists.” Gradually, she moved away from the dream imagery and Surrealist techniques of her early art practice to a new focus on the “visually immediate” world around her. Paintings and drawings of this period reflect Sterne’s new American environment: her kitchen, bathroom, and stove, New York’s buildings and street scenes, cars and subway tracks. As she would say, “I became visual when I came here.”

Gestural Abstraction

In the 1950s, Hedda Sterne’s work grew increasingly abstract and gestural. She found aerosol spray paint — new to hardware store shelves in the early ‘50s — an ideal medium for expressing a sense of speed, light, and motion in her paintings. These works are often viewed in the context of Abstract Expressionism, and Sterne’s own philosophical approach to painting was closely aligned with what her friend, art critic Harold Rosenberg termed “Action Painting” in 1952. As an artist, she felt, “you will find no rest until you possess whatever knowledge of your medium there is to be had.”

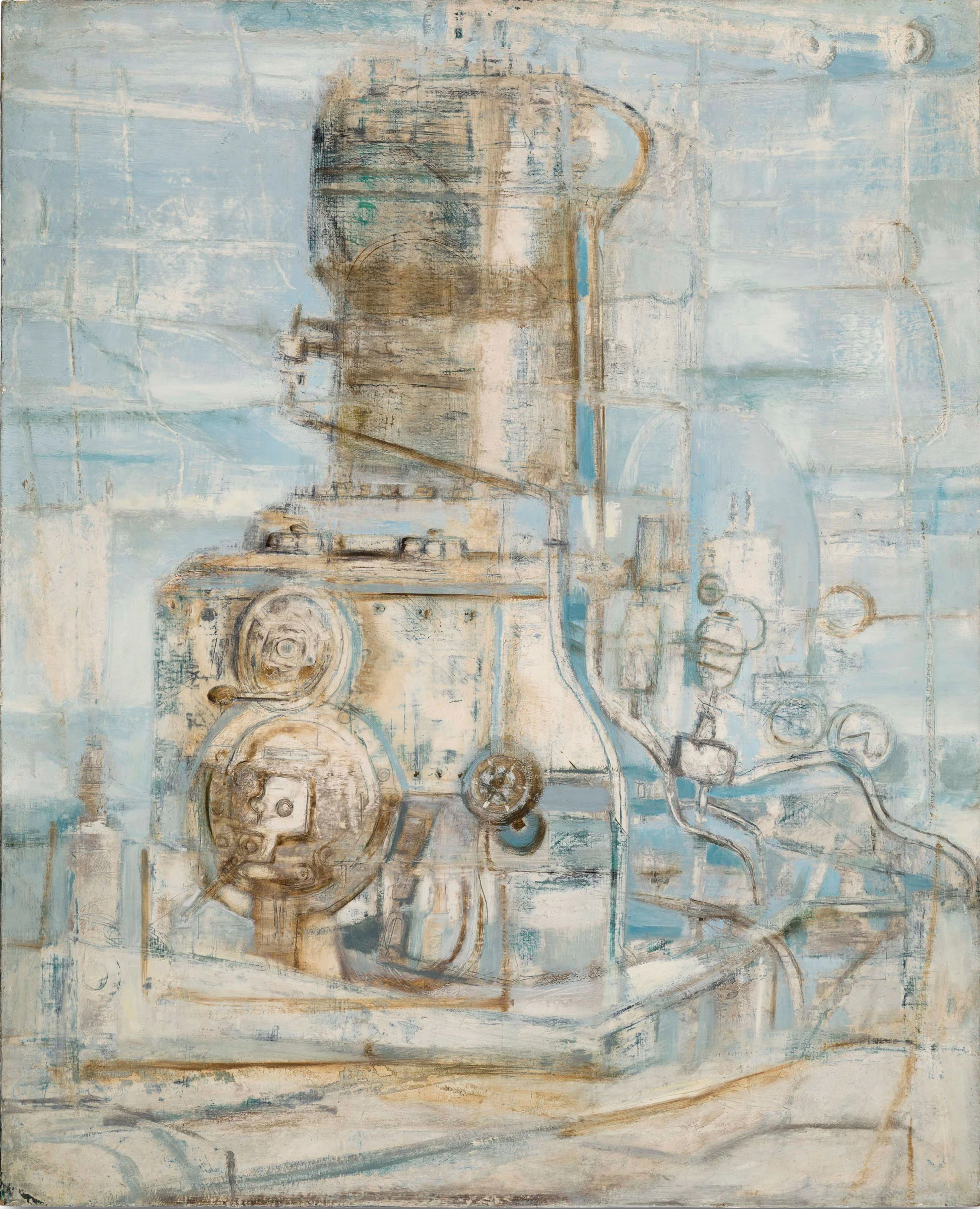

Machines & Anthropographs

Hedda Sterne’s interest in the visual aspects of post-war America reached its zenith in her “Machine” paintings of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Abstractions of agricultural equipment, airplane machinery, and massive postwar construction sites reflected the inadvertent beauty she found in the man-made world. She coined the word “anthropograh” to describe certain paintings and drawings composed like portraiture. Sterne saw the human-like design of many machines as “unconscious self-portraits of people’s psyches.”

Hedda Sterne, Machine (Anthropograph I), 1949, Oil on canvas, 29 1/2 in. x 39 in., Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Purchase, Gift of Samuel Dretzin, by exchange, Bequest of Gioconda King, by exchange, Rogers Fund, by exchange, Funds from various donors, by exchange, and Gift of Chauncey Stillman, by exchange, 2017

Philosophy & Meditation

Hedda Sterne was an avid student of philosophy throughout her life and would find new ways of discovering “facets of reality” through her private studies, which would in turn affect her art. She maintained a daily practice of meditation starting in the mid-1960s, and around the same time began centering her art on internal reflections and theories of the mind. Several bodies of work trace back to Sterne’s varied interests, from metaphysics and semiotics, to Zen Buddhism and Christian mysticism.

Portraiture

Hedda Sterne shifted between abstract and figurative modes of expression in her art practice. “I took it for granted,” she would say, “that art is essentially an act of freedom. You react to the world totally freely.” At times, she would find herself preoccupied with painting and drawing portraits of friends, including many of the artists and writers within her milieu. Sterne traced her recurring interest in portraiture to her early childhood when she discovered her interest in drawing and creating “good likenesses.”

![Hedda Sterne, Untitled [ Airplane cockpit ] , 1949, trace monotype, 15 7/16 × 10 3/8 in., Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Purchase, with funds from the Print Committee 2007.11](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/586d344215d5dbe77c2087cf/1494346255340-8F302GXLB9IUOH884PSJ/hedda-sterne-monotype-whitney.jpg)

![Hedda Sterne, Portrait of Saul [Steinberg], 1943, Graphite on paper, 12 in. x 8 3/4 in.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/586d344215d5dbe77c2087cf/1494345446206-ETD0P3RFU8YOZUMXQ8DG/hedda-sterne-drawing-0254.jpg)

![Hedda Sterne, G.D. [John Graham], 1943, Oil on canvas, 39 x 31 in.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/586d344215d5dbe77c2087cf/1494345468570-IASOQMSDDNSOWGU0DAHH/hedda-sterne-painting-2536.jpg)